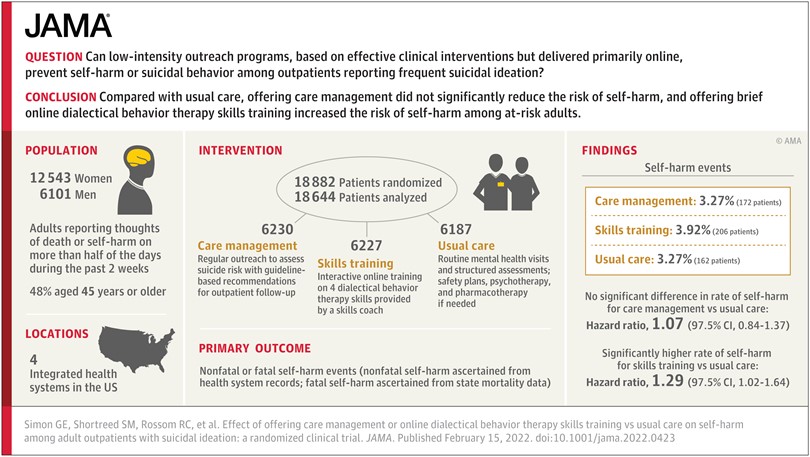

We recently published the results from our large pragmatic trial of outreach programs to prevent suicide attempts. Neither of the programs we tested reduced the risk of self-harm, and one of them (an online program to introduce four skills from Dialectical Behavior Therapy or DBT) appeared to increase risk. We were surprised and disappointed by those results. But we double- and triple- and quadruple-checked our work. And those definitely are the results.

As we’ve shared those results with various colleagues and other stakeholders, their first responses reflected the early stages of grief: Denial (“There must be mistake here.”) and Bargaining (“We just need to look in the right subgroup.”). We passed through exactly the same stages, but we’ve had more time to get to acceptance. Acceptance meant publishing the results without any equivocation: These programs were not effective. One may have caused harm. And those results held across all sorts of secondary and subgroup analyses.

After our paper was published, the Twitterverse had plenty of hot takes: “How can you call this DBT?!” (We didn’t say that). “This proves that all brief online interventions are worthless or risky!” (We certainly didn’t say that). But hot takes on Twitter are not the best place to make sense of something disappointing or upsetting.

We are still sorting out our cooler take on the trial results. We suspect that any negative effect of repeatedly offering the online skills training program came not from the skills, but from repeatedly offering what some people found unhelpful. Risk of self-harm was highest in people who initially accepted our invitation to the program and then quickly disengaged. One disadvantage of communicating by online messaging is that our skills coach couldn’t tell when repeated offers – however well-intentioned – were causing more upset or disappointment.

The one hot take that did bother me was from the Anger stage of grief: “How could you have done such an unethical study?!” Our trial certainly would have been unethical if we had known or strongly suspected that the programs we tested were ineffective or harmful. But the opposite was the case. We hoped and believed that low-intensity interventions delivered at large scale could reduce risk of self-harm and suicide attempt. Many other people in the suicide prevention field hoped and believed the same thing. We were wrong. Now we know. Before we didn’t. That’s why we do randomized trials.

Greg Simon