As MHRN investigators, we often hear from academic researchers hoping to study new psychotherapies or eHealth interventions in our healthcare systems. Those new interventions typically focus on a specific diagnosis (like obsessive-compulsive disorder) or patient subgroup (like depression in people with arthritis). But when we bring these ideas to leaders in our care delivery systems, their interest in these specific interventions is often low. Our health system partners are typically more interested in broader care improvements – like measurement-based care for depression or addressing suicide risk across all diagnoses.

It’s not surprising that researchers based in academic health centers focus on more specific interventions. Care in academic centers is more often organized around subspecialty areas like obsessive-compulsive disorder or depression in rheumatoid arthritis. And the typical path of an intervention researcher (from dissertation topic to post-doctoral fellowship to career development award) emphasizes finding a specific clinical niche. The research grant review process also demands specificity – even if our diagnostic categories are much fuzzier and overlapping than we like to admit.

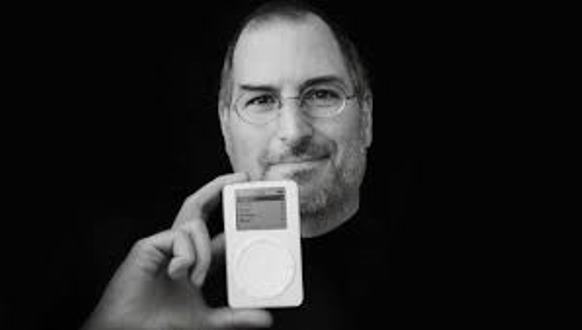

Thinking about the value of more specific interventions reminded me of a recent New York Times column proclaiming that “The Gadget Apocalypse Is Upon Us”. The premise of the column was that previously separate electronic gadgets have been swallowed by mobile phones. That premise does seem true for MP3 players, GPS devices, and point-and-shoot cameras. iPods have certainly faded, and only the most serious photographers now carry around separate cameras. The music-playing and direction-giving and picture-taking features built into our mobile phones are good enough for most of us. But not all separate gadgets have disappeared. Wrist activity monitors seem to be doing just fine. And new families of gadgets (like the Google and Amazon voice-controlled speakers) are still emerging. A separate gadget that meets the right need at the right time can still succeed. Those successful gadgets beg the question: When is a specialized or dedicated tool (like a narrowly targeted mental health intervention) worth the extra effort or expense?

Asking that question about a new electronic gadget begins with the assumption that nearly everyone is already carrying a mobile phone. So we’d only carry around a separate gadget if it really improved quality or efficiency. A dedicated camera can take nicer pictures than my phone. And a wrist activity monitor might save me from carrying my phone on a run.

In the same way, asking our MHRN care systems about testing or implementing a specific mental health intervention begins with the assumption that a “generic” mental health infrastructure is already in place. Geographically organized clinics are staffed with psychiatrists, nurses, psychologists, and other psychotherapists. Those clinicians serve people seeking care for the full range of problems or diagnoses. We would want to implement more specific treatments or programs if those specific treatments had real advantages – in either quality or efficiency – over the general-purpose treatments we are already providing. It would not be convincing to show that a specific treatment or program is superior to no treatment or some “placebo” condition. Instead, it would be necessary to show advantages over existing general-purpose treatment. And the benefit of that new clinical “gadget” would have to be large enough to justify the extra expense or effort.

I’m finally getting to the topic of coordinated specialty care for first-episode psychosis. We have clear evidence that coordinated programs improve outcomes compared to general-purpose care in community mental health centers. In this case, the coordinated specialty care “gadget” probably does have real added value. But our behavioral health leaders have not shown much interest in implementing specialized programs. Our MHRN research shows that first presentations with psychotic symptoms are not rare in our health systems. While initial engagement in care is high, over half of young people with new-onset psychotic symptoms have dropped out of mental health care within a few months. From where we (MHRN researchers) sit, it looks like our health systems need a dedicated gadget to improve care for first-episode psychosis. Now we have some marketing to do – convincing our health system partners that a specialized program would be useful enough often enough to justify the extra effort.

Greg Simon