I have a beef with the name “Social Determinants of Health”.

I absolutely agree with putting the word “social” right up front. It’s a fact that zip code often has a greater effect on health than genetic code. And the effects of social and environmental factors – such as trauma, loss, and deprivation – are especially relevant to mental health.

It’s the specific word “determinants” that I’d want to change. Social factors often have powerful negative or positive influences on physical and mental health. And the effects of social and environmental factors can certainly overwhelm the treatments we provide. But the impacts of social and environmental factors are almost always probabilistic rather than deterministic. The term “social determinants” may sound more powerful than “social influences”, but it is also less accurate. And the difference between “determinants” and “influences” is not just semantic hair-splitting.

Adopting a deterministic – rather than probabilistic – view of social influences on health can distract us from places where our research can actually make a contribution. When we study risk or causation, only a probabilistic view will allow us to understand individual variation in vulnerability and resilience. In statistical terms, true understanding requires us to move beyond simple questions regarding main effects (Does a specific environmental insult matter on average?) to questions about interactions (For whom does that insult matter more or less? Under what conditions is the health impact larger or smaller?). When we examine those interactions, will likely find that the impact of social and environmental insults is even greater among the vulnerable or disadvantaged – those who have already experienced trauma, loss, and deprivation.

When we develop or test interventions, a probabilistic view focuses us on disrupting specific linkages between social or environmental insults and subsequent mental health problems. Here again, we can think of interventions as effect modifiers or interactions rather than simply main effects. For example, we certainly hope that the association between childhood victimization and adult PTSD is not deterministic. Instead, we hope it can be modified by timely and specific intervention. Embracing probabilistic complexity should help us to identify interventions to support the most vulnerable by disrupting causal pathways with the biggest public health impact. That probabilistic – rather than deterministic – view will usually direct resources to those with greatest need. For example, interventions to address the long-term effects of early childhood trauma will likely have greatest benefit in those who were already disadvantaged.

A deterministic view can easily lead to what my colleague Evette Ludman and I have called sympathetic nihilism. By that, we mean a well-intentioned but ultimately dispiriting focus on all the reasons for illness and disability – rather than a search for paths to recovery. Mental health care too often falls into that trap of sympathetic nihilism.

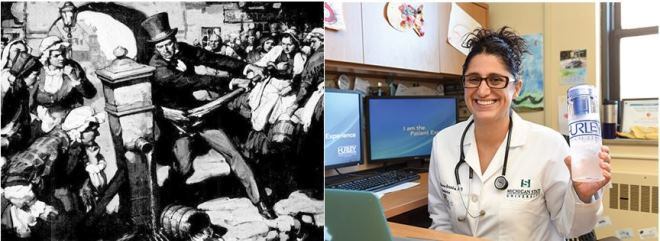

Nevertheless, deterministic thinking can be appealing. We would all hope to emulate John Snow, the London physician who interrupted an 1854 cholera epidemic with a single dramatic act, removing the handle from the contaminated Broad Street water pump. In our modern times, social and environmental insults rarely have a single point source. Instead, the sources of harm are more systemic.

Our closest modern analogue of John Snow is probably Mona Hanna-Attisha, the pediatrician who revealed the devastating effects of lead-contaminated water in Flint, Michigan. She certainly did advocate for immediate action to interrupt ongoing lead exposure, but there was no single pump handle to remove. She understood that toxic lead levels in children’s drinking water reflected a complex interaction of governmental decisions about water sources, decaying public infrastructure, and outdated plumbing in individual homes and schools. The lead poisoning epidemic had no single point source. So she advocated for governmental action to address systemic problems and educated individual families about reducing exposure. She also realized that controlling every source of contamination would not reverse the chronic effects of childhood lead exposure. Repairing those adverse developmental and mental health effects will require long-term therapeutic and rehabilitative interventions. Even if we could find and remove that magic pump handle, many children will be affected for decades to come.

None of us working in mental health will likely face that dramatic and deterministic John Snow scenario. Instead, like Mona Hanna-Attisha, we regularly face complicated probabilistic scenarios. To address that complexity, we are called to a range of responses. Appropriate responses will often include both advocacy to address systemic social causes of poor mental health and a search for effective therapeutic and rehabilitative interventions. While we will rarely discover that that point source of cholera to eradicate, we can aspire to discover and deliver the mental health equivalent of oral rehydration for cholera – an intervention that’s surprisingly effective, rapidly scalable, and easily affordable. Developing an effective and scalable intervention certainly does not negate or undermine every person’s right to safe drinking water. But it does help those who are already sick.

Greg Simon