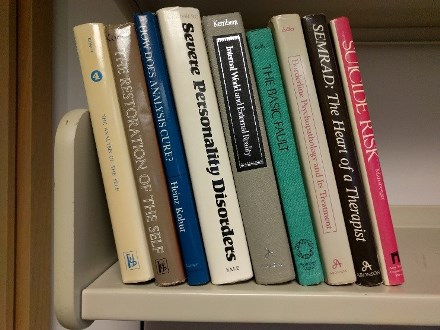

Last month I moved to a temporary office to make way for painting and installing new carpet. Being forced to pack up every book and file folder was actually a good thing. I recycled stacks and stacks of paper journals. Saving those was a habit left over from the last century. I cleaned out file drawers full of old paper grant proposals and IRB applications, relics from the days before electronic submission. I purged stacks and stacks of paper reprints (remember those?) from the 1990s. I recycled books I hadn’t opened in 15 years. Tidying up did feel good, but my purging frenzy paused when I came to this stack of books from my residency days.

Those old books were a greatest hits collection from some of the legends of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Some of the authors were my own teachers (Jerry Adler, Terry Maltsberger). Some were the heroes of my teachers (Heinz Kohut, Michael Balint, Otto Kernberg, Elvin Semrad). Thirty years ago, those books were central to my thinking, or even my identity. But I hadn’t opened any of them since my last office move in 1999.

I paged through a few of them, trying to remember what had been so valuable back then. From my current perspective, I can’t say that psychoanalysis, or even psychoanalytic psychotherapy as practiced in 1980s Boston, can really succeed as a public mental health strategy. As a care delivery model, psychoanalysis scores poorly on all three of my “three As” tests. It’s not really affordable. It’s unlikely to ever be widely available. And it’s not always acceptable to the diverse range of people who live with mental health conditions.

But there is still some valuable wisdom in those old books. Studying Kohut certainly helped me to understand how a fragile sense of self disrupts emotion regulation and how persistent empathy can help to rebuild self-regulating capacity. And studying Kernberg helped me to understand the nonlinear relationship between the internal mental world and external reality. The persistent outreach and care management interventions that we now develop and evaluate do owe a significant debt to those psychoanalytic legends – and most especially to Kohut and Semrad.

So my psychoanalytic books survived this office move. To borrow some psychoanalytic terms, they continue to serve as healthy introjects. I’ll keep holding on to them as transitional objects.

Greg Simon